9

EPISODE NINE : ISLAND OF HAWAI’I

The Island of Hawai’i, colloquially known as the Big Island, is the largest in the archipelago but home to less than 15% of the state’s total population. Many Kānaka Maoli have resisted colonial encroachment and taken to the island’s hinterland to reclaim an ancient way of life, where the people care for the land and the land cares for them. Meet Alika and Lacyann, who, by rekindling family traditions, have given purpose to their lives and inspired future generations.

OUR STORYTELLERS

ALIKA

LACYANN

OUTRIGGER CANOE

wa’a

(Hawaiian)

A famous Hawaiian proverb reads, “He wa’a he moku, he moku he wa’a — a canoe is an island, an island is a canoe.” The outrigger canoe, or wa’a, is at the very core of Hawaiian identity; if it were not for the canoe, Hawai’i would not exist.

Polynesians have a maritime tradition going back thousands of years, making their journey from mainland Asia through the vast Pacific Ocean and eventually arriving in the Hawaiian Islands around 1,000 years ago.

The early Polynesians were able to cross the world’s largest ocean thanks to their innovative outrigger canoes. These allowed them to sail for many months, guided by their advanced navigational technology using the ocean, wind and stars.

Once Hawai’i was settled, the wa’a remained a part of daily life due largely to the islands’ harsh interior terrain, making them essential for travel. The people used them to fish, transport goods and travel across the archipelago, resulting in a wide variety of canoes being developed.

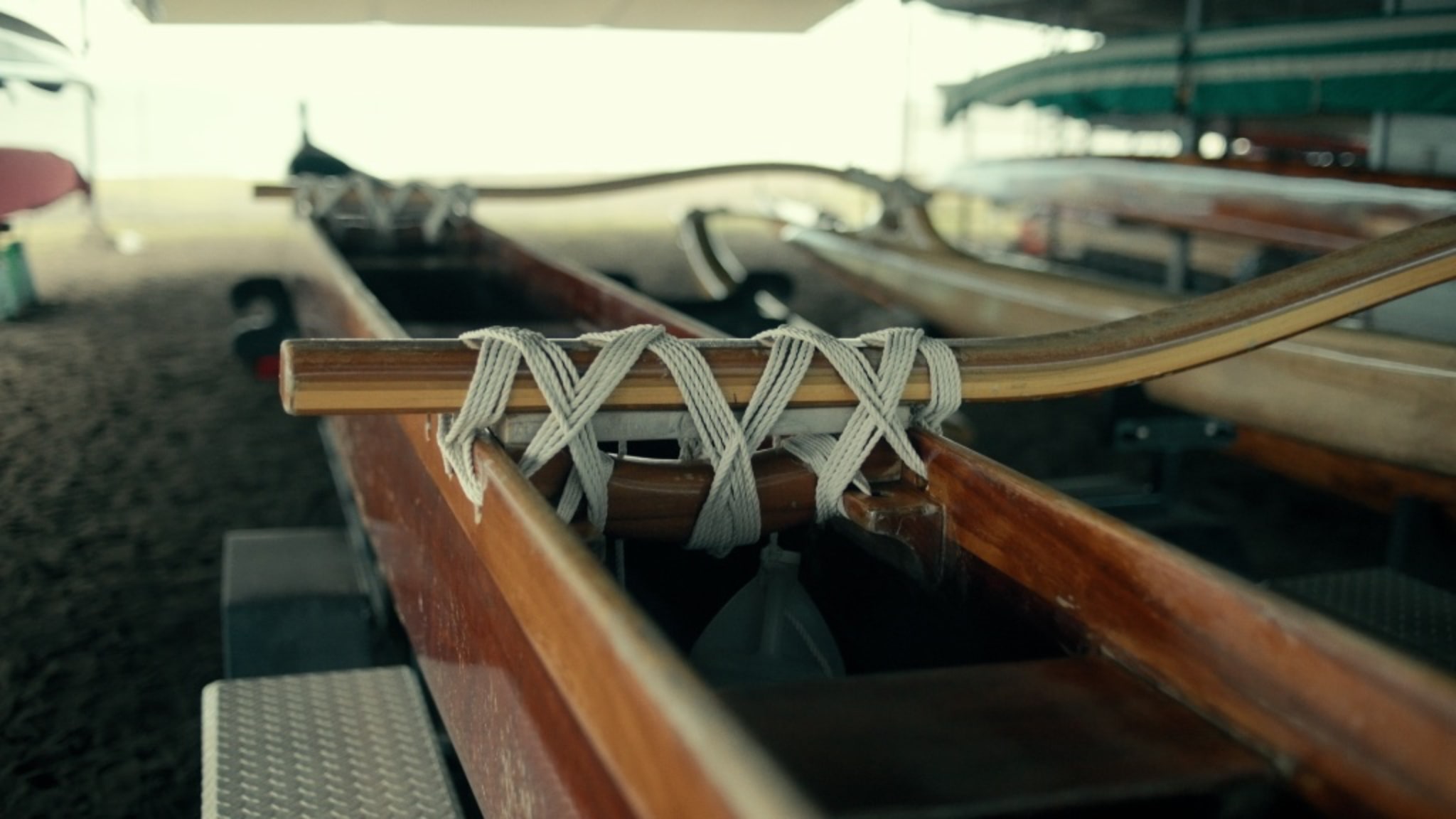

Many of these boats were made from the now-endangered koa tree, which is large enough to yield an entire canoe. The construction process was a communal effort steeped in religious ritual, with a kahuna, or priest, selecting the tree and participating in the entire carving process.

Much of this knowledge was passed down through families who developed their distinctive traditions, such as unique crossbeam lashing patterns that tie the outriggers to the hull.

The colonial period and expulsion of Kānaka Maoli from the coast led to many wa’a going unused, resulting in the open-ocean voyaging culture nearly disappearing.

In the early 1970s, Hawaiian voyaging traditions were revived when the Polynesian Voyaging Society launched their double-hulled wa’a, the Hōkūle’a. In 1975, the vessel sailed from O’ahu to Tahiti, a feat not accomplished in over 600 years.

Today, many young Hawaiians are learning about these age-old traditions by joining rowing clubs, carving apprenticeships, sailing schools, and voyaging societies, as well as learning and perpetuating traditional practices for future generations.

CONTACT US

Have a story about your own little big community?

Reach out and let us know! We would love to help you tell it.